WELCOME TO HEAD & NECK ROBOTIC SURGERY

Advancing minimally invasive surgery with cutting-edge robotic systems for safer, faster, and more effective treatments.

A revolution is unfolding in the world of surgery, one that is poised to redefine how we approach the operating room. It began with an ambition to perform medical procedures across distances where patients and caregivers were not physically close. DARPA and NASA funded the original research for obvious interests—bringing robotic precision to situations far from conventional surgical settings.

This led to the development of the first telemanipulated robotic surgery devices. Milestones such as the Zeus robot and the early prototypes of the da Vinci system paved the way for the first da Vinci standard, and a new era in surgery started.

In the early 2000s, Greg Weinstein and Bert O’Malley at the University of Pennsylvania saw untapped potential in these systems. They pioneered a groundbreaking application: Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS), which revolutionized the surgical approach to the oropharynx. By harnessing the enhanced 3D visualization and precision of robotic arms, they developed a minimally invasive technique that redefined minimally invasive head and neck surgery.

Similarly, a desire for less invasive procedures—driven initially by cosmetic concerns—spurred the development of remote-access techniques for the neck. This evolution demonstrated that robotics could push surgical boundaries even in fields like thyroid and parathyroid surgery, where outcomes were already excellent.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is now ushering in the next chapter of this revolution. At its core, AI refers to a machine’s ability to mimic human intelligence, while machine learning (ML)—a subset of AI—uses data to identify patterns and improve task performance over time. Deep learning (DL), a type of ML, employs neural networks with multiple layers to process data in increasingly sophisticated ways.

This year’s 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics celebrated the foundational work that contributed to make modern AI possible. Is was awarded to John J. Hopfield (Princeton University) and Geoffrey Hinton (University of Toronto) “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks”. Hopfield’s pioneering research making neural networks able to share and recreate patterns (1982) and Hinton’s machine that learnt to recognize characteristic elements in a set of data (1983) laid the groundwork for AI-driven image processing—one of the cornerstones of surgical innovation today and a basic tool for machine learning.

Does it sound too abstract?

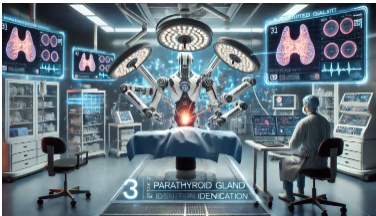

Consider PTAIR 2.0 (Parathyroid gland Artificial Intelligence Recognition) (doi: 10.1002/hed.27629), a deep learning model that enhances parathyroid gland identification during endoscopic thyroidectomy. This system surpasses even experienced surgeons in real-time recognition and ischemia assessment. Using continuous image processing, it identifies gland locations, marks them, tracks them, and issues alerts when ischemia occurs. This information, presented via augmented reality (AR) on surgical monitors, represents a potential monumental leap forward in safety and precision.

Or Surgical Robot Transformer. It is is a joint research of Johns Hopkins University and Stanford University on surgical robot automation. They could teach an AI to perform basic surgical tasks using a da Vinci Si patient-side cart. How did the AI learn surgery? By imitation learning. A large repository of clinical data (surgical videos), which contains approximate kinematics, was directly utilized for robot training without further corrections. That is, the robot (an AI with effective arms), learnt surgery by seeing surgery. This is machine learning. It is not current tele-manipulation, is the beginning of autonomous robotic surgery.

The theoretical framework for autonomous robotic surgery has existed for over four decades. What we lacked was the technology to bring it to life. Today, we stand on the cusp of this reality, equipped with the tools to accelerate progress.

The pace of innovation is about to skyrocket, and the implications for patient care, surgical training, and global health are profound. As professionals and as a society, we must be ready to adapt to this new era of medicine.

The revolution in robotic surgery isn’t coming—it’s here. And it’s reshaping the future before our eyes.

J Granell. December 2, 2024.